It’s probably fair to say that everyone, at some point in their life, wonders what it would be like to discover something amazing. How would it feel to be the person to stumble upon an artifact, a piece of history, a relic from another time?

James Procell, director of the Dwight Anderson Music Library, recently found out. On a whim, he discovered the only known handwritten manuscript of the world’s most popular song: “Happy Birthday.”

It all started about seven years ago when Procell noticed a folder labeled “Mildred Hill” filed away in the library’s archive room. The folder had come into the university’s possession by way of Hattie Bishop Speed’s estate; the Hills and Speeds were close friends and contemporaries. “I knew who she was and that she’d written the song. But I just assumed it [contained] newspaper articles that had been written about her, so I didn’t really think much about it,” Procell said.

But when “Happy Birthday” starting making headlines because of a recent high-profile copyright lawsuit, he thought the folder might be worth a second look.

“I thought, ‘well, let me take this out and see what’s in this folder.’” Sandwiched between hundreds of other documents, he found a small sketchbook. “I opened it up and saw the words… and thought, ‘Oh gosh. This is a pretty big deal.’”

About the Manuscript

The birthday song as we know it today is derived from the song “Good Morning to All,” written by Mildred and Patty Hill, of Louisville, in 1893. Mildred was a composer and musicologist. Patty, a kindergarten teacher, composed songs for her students. Both women made a big impact in their respective fields.

Several theories attempt to explain how “Good Morning to All” evolved into “Happy Birthday to You.” Some theories involve a third Hill sister, Jessica. Other theories point toward an organic evolution that just happened. Regardless, it is widely agreed that the Hill sisters’ “Good Morning to All” birthed the now ubiquitous birthday song.

This particular manuscript — along with other contents in that understated, tucked-away folder — provides some interesting clues about the Hill sisters’ writing process and the song’s history.

For starters, page one is missing, making the specific date of Mildred’s transcription unknown. But based on the dates written on other pages of the sketchbook, Procell thinks this is actually a revision of the well-known version published in the 1893 book “Song Stories for the Kindergarten.”

“I think this is Mildred’s attempt to make the song a little easier,” Procell said. “Mildred would compose these songs. Patty would bring them to her students, and then bring them back to Mildred to edit.”

The version in this sketchbook is notably easier to sing, as it avoids that almost-always butchered octave jump toward the end.

The Women Behind the Music

Mildred Hill: Musicologist, Trailblazer

Despite having composed the world’s most popular melody, Mildred Hill’s contributions to music history are often forgotten.

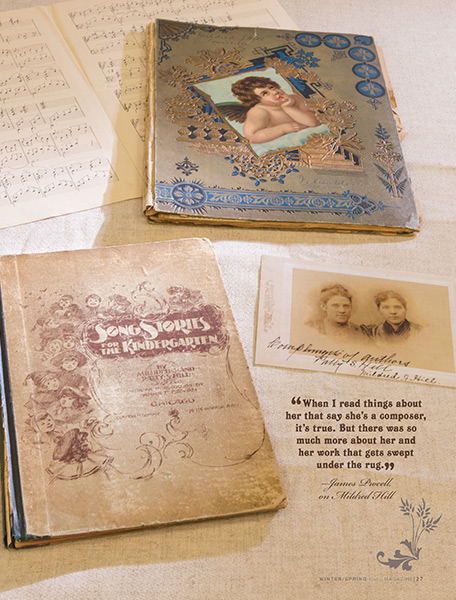

Mildred, like all of her siblings, was encouraged by her parents to take up a profession and be self-reliant — an eccentric notion for the time. She followed her passion for music and, as her notes, diaries and manuscripts reveal, studied slave spirituals and African-American music with fervor. Perhaps the most visually stunning piece found in the UofL music library is one of Mildred’s scrapbooks, which holds newspaper clippings and other research related to slave and folk music. On the cover, she wrote “Very important,” underlined three times. Notably, her work predates the dawn of the jazz era, making Mildred a true trailblazer.

Luckily, her ideas on the value and importance of slave music were not kept hidden in diaries. In 1893, her article titled “Negro Music,” appeared in “Music: A Monthly Magazine” under a pseudonym, Johann Tonsor. (Like many notable women in history, Mildred chose a male name to eliminate unfavorable gender-bias in a male-dominated fi eld.) It is well documented that her article’s emotional and musically technical descriptions of slave songs strongly inspired Antonin Dvorak’s “New World Symphony.”

UofL’s music library contains Mildred’s transcriptions of many types of music, including hymns, educational songs and chamber music, proving that she was a serious composer, collector and musicologist in her own right.

Patty Hill: Educational Innovator

As both an educator and child-welfare activist, Patty Hill was an incremental reformer of early-childhood education. When Patty began her studies, kindergarten was a highly structured environment where the primary pedagogical emphasis was in cognitive development. Patty, however, saw that many common kindergarten tasks, such as sewing, weaving paper and playing with small blocks, were too complicated for such young students.

According to UofL professor emeritus and Patty Hill scholar, Ann Taylor Allen, Patty set out to create a more comfortable and effective learning environment. She introduced freehand drawing and painting. She increased outdoor playtime, she required students to take naps, and she provided healthy snacks and school nurses. The fact that these activities sound commonplace now attests to how influential her methods have proven to be. Patty’s influence stretched well beyond the four walls of her kindergarten classroom; she played a vital role in providing free education for the underserved and immigrant populations of Louisville. It was in these classrooms where “Good Morning to All” would have been sung, and possibly where the “Happy Birthday” lyrics were born.

To that end, the “Good Morning to All” manuscript discovered at UofL reveals a glimpse into Patty’s teaching philosophy. The manuscript is slightly different than the previously-published version, suggesting that Patty and Mildred altered the tune to be easier for her students to sing. The fact that a teacher would go to such great lengths to accommodate her students shows that Patty saw them not as children in need of training, but as people in need of empowering.

A Piece of Global Interest, Right Here at Home

Despite giving countless interviews on Mildred and the manuscript, Procell takes surprisingly little ownership for such a major discovery. “I just happened to be the one who came in [the archive room]. I wasn’t really even looking for it,” he said.

But for the rest of the world, there’s something exciting about this discovery. Procell recounts that for over two weeks his phone rang non-stop. During that time he spoke with some of the world’s biggest news organizations and attempted to answer every email that hit his inbox. He feels that the attention is giving the University of Louisville global prestige.

“We have many valuable and special collections here. But I think this one, with it receiving so much national and international press coverage, really brings a lot of positive attention to the university,” Procell said. “I’m really honored to be a part of it.”

Admittedly, Procell knew little about the Hill sisters before discovering Mildred’s papers, but he now plans on honoring her legacy with a concert of her works in 2016. In the meantime, he’s seeking donor funding to help digitize her papers, which would both preserve her work and make it accessible to all.

containing research on slave spiritual music and a fi rst-edition run of the popular

“Song Stories for the Kindergarten.” Photo of Mildred & Patty Hill, not found in archives.