Many Kentuckians claim Abraham Lincoln as one of their own because he was born in Hodgenville, Kentucky. However, the 16th president of the United States isn’t just tied to the state of Kentucky — he is also rumored to have connections to UofL.

Online bios of both Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, and Lincoln’s brother-in-law, Benjamin Hardin Helm, say these two Lincoln connections attended UofL’s law school in the mid-1800s.

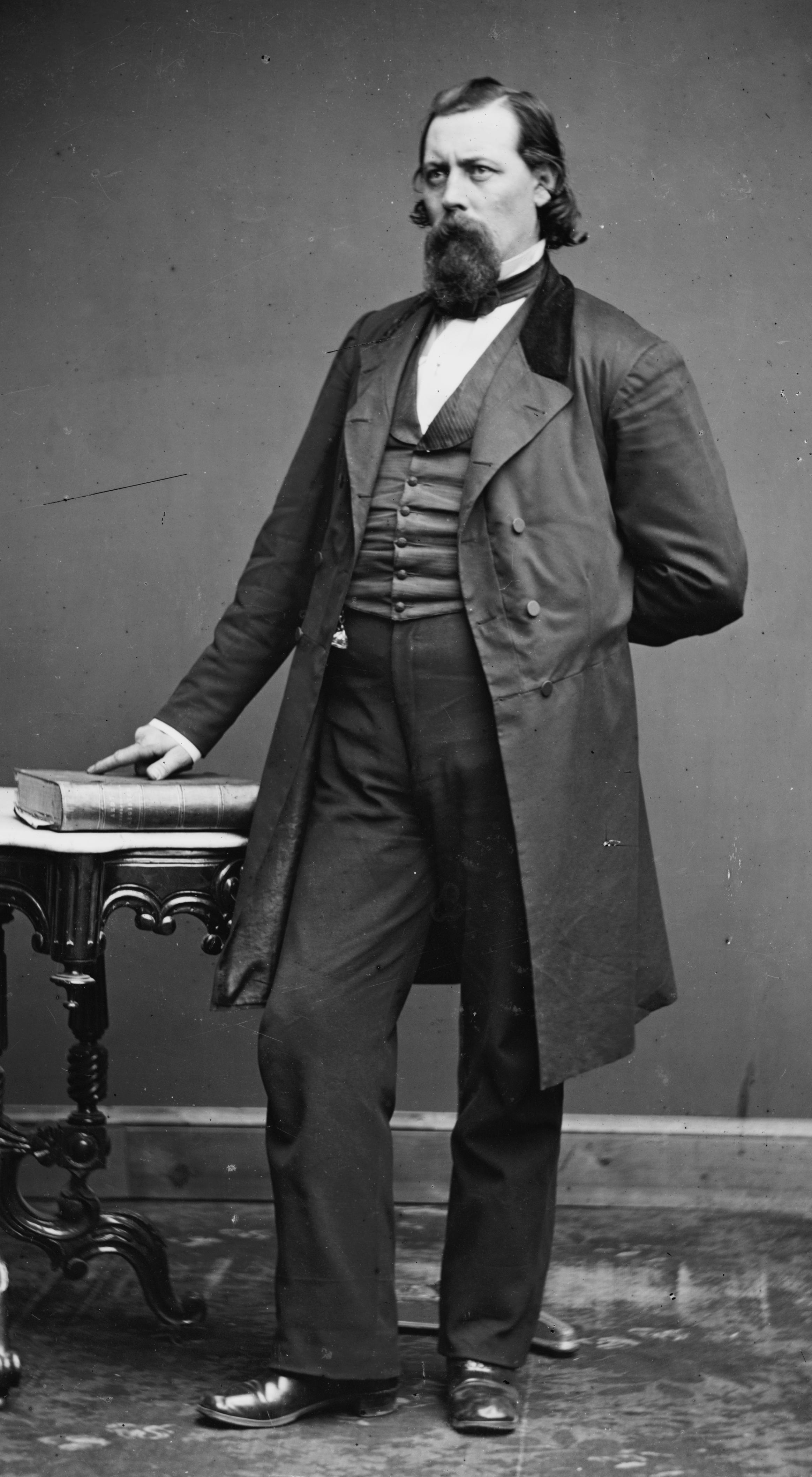

Lamon was a close friend and self-appointed bodyguard of Lincoln. Born in 1828 in Virginia, he pursued the study of medicine as a teenager but soon abandoned medicine for law. When he was 19, Lamon moved to Illinois and, according to bios, later attended lectures at Louisville’s law school.

An 1850-51 study directory the university’s Law Library purchased from a rare-books dealer provides a clear indication that his claim to Cardinal fame is true.

The directory lists W. H. Lamon of Martinsburg, Virginia, in its “catalog of students in the department since its founding.” In 1851, Lamon was admitted to the Illinois Bar, which also included Lincoln, who became one of Lamon’s fast friends. Lamon, who was described as a burly, boisterous man, chose to act as Lincoln’s bodyguard during his presidency. Because Lincoln sent Lamon on an errand in Richmond, Virginia, Lamon was absent from Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was assassinated.

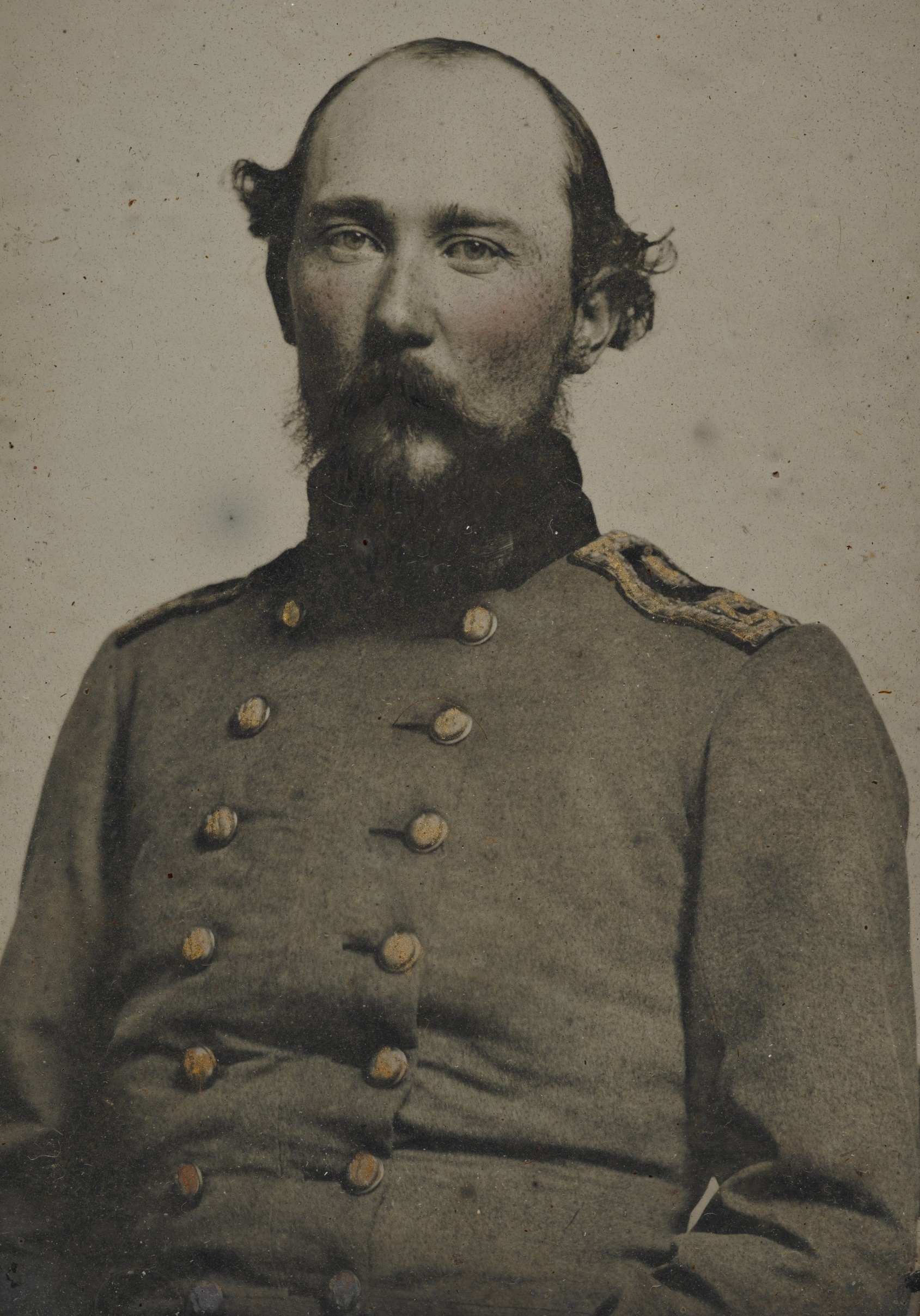

Around the same time Lamon was attending lectures, Helm was also studying law. Lincoln’s brother-in-law was an attorney and a brigadier general for the Confederate Army. Born in 1831 in Bardstown, Kentucky, Helm married Emilie Todd, a half-sister of Mary Todd Lincoln, in 1856. Lincoln offered Helm the position of paymaster for the Union Army, but Helm declined the offer and moved forward with the Confederate Army. Helm died at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863 while commanding the First Kentucky Brigade, commonly know as the Orphan Brigade.

Helm’s history with UofL is a bit murkier than Lamon’s. A 1943 biography, “Ben Hardin Helm, Rebel Brother-in-law of Abraham Lincoln,” says Helm received his law degree in 1853. But according to Kurt Metzmeier, associate director of the law library, Helm is not listed in the 1850-51 catalog of UofL law students. However, this only proves Helm did not attend lectures before November 1850.

According to Metzmeier, during the mid-1800s attending law school was not a requirement to become a lawyer.

“Lawyers of this area typically ‘read law’ under another attorney, which was essentially an apprenticeship,” he said.

Apprentices would then appear before a judge to be quizzed on the law and, if satisfied, the judge would grant them a law license.

“Attending law lectures was an extra bit of polish to the process of reading law, usually undertaken by those who could afford it to show status,” Metzmeier said.

Metzmeier said the only other law school in the region at the time was at Transylvania University and UofL was one of only three or four law schools west of the Appalachians. UofL’s law school was well-respected in the law community during the era, which would have encouraged such prominent men as Lamon and Helm to stop by for a lecture, he added.

And what about Lincoln himself?

“Unlikely,” Metzmeier said. “But with Lincoln’s friend (and future U.S. Attorney General) James Speed on the UofL board of trustees in the early 1850s and on the law faculty from 1856 to 1858, it is at least possible to imagine the lanky Illinois lawyer stretched out in a doorway waiting for his old friend to finish a lecture or some university business.”